About Thomas Barlow

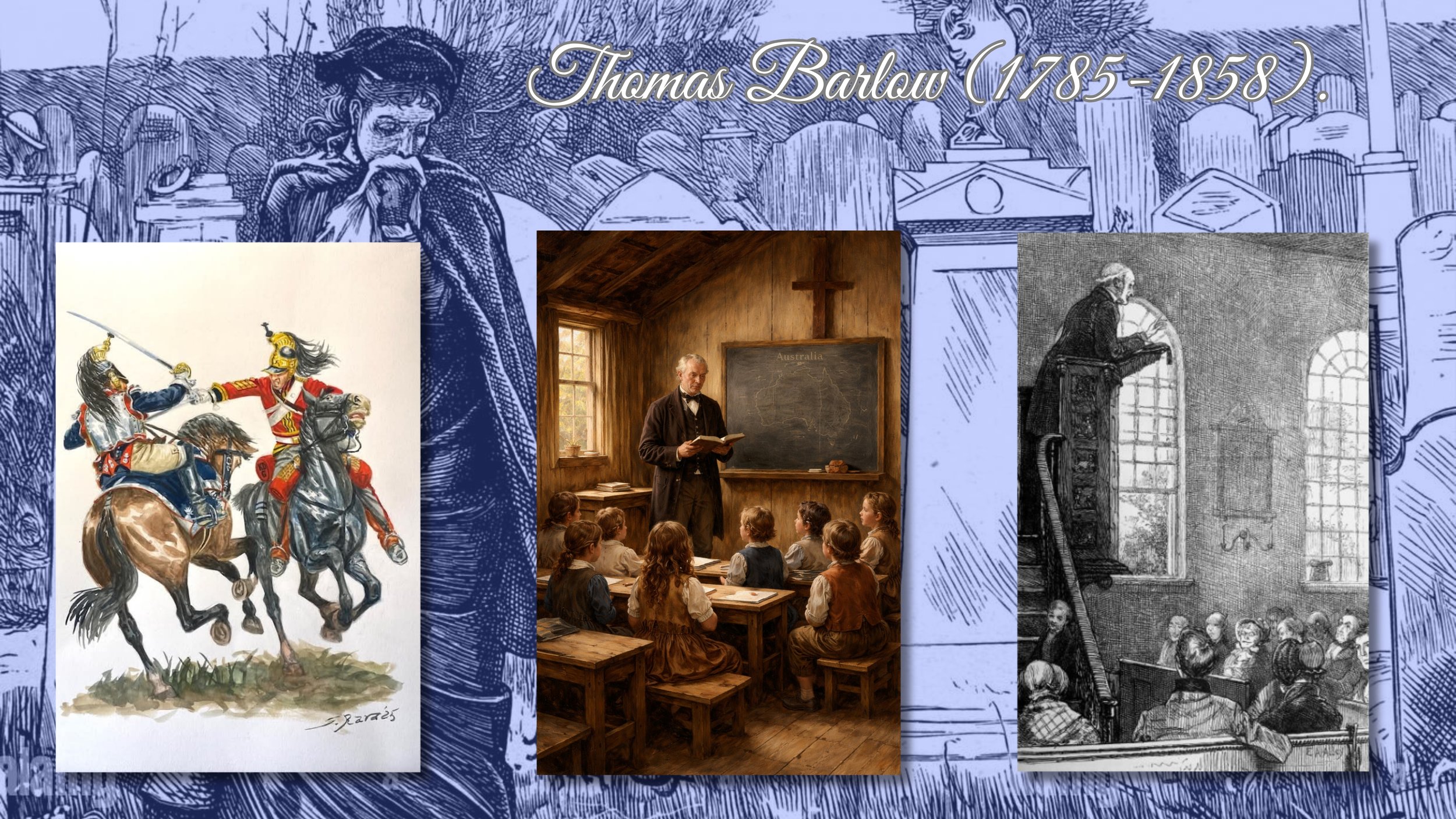

Thomas Barlow (1785-1858)

Little is known about the origins and boyhood of Thomas Barlow apart from his birth in Yorkshire c1785. At the age of sixteen on 18 April 1801 he joined the Kings Dragoon Guards as a private.

Seemingly ambitious from the first, Thomas became a corporal in 1805, sergeant in 1807 and Troop Sergeant Major in 1811. He was Regimental Sergeant Major in 1815 when the Regiment embarked for the Low Countries.

Despite the war with France, he saw military service in relatively peaceful places in England and Ireland. From 1801 to 1802 he was stationed in the Midlands; from 1802 to 1804 in Southwest England; between 1804 and 1808 in Sussex, moving North until 1811 when the Regiment was sent to Ireland. It was here that he married his first wife, Elizabeth Wagstaff, the daughter of William Wagstaff, Quartermaster of the regiment, and Ann Reid of Bradford. It is in his letters* to ‘Betsey’ from the campaign that he not only details his part in the battle of Waterloo, but also describes his day-to-day army life, his affection for his young wife and plans for their future life together. The following quotes are from a letter written on May 16 from St Levins Efsche.

“...my earnest prayer is that we may live long together, and enjoy the society of each other, in peace and joy, crowned, with every blefsing we can expect to make us happy, and filled with an afsurance of an eternal felicity-I certainly am ambitious as it respects earthly honours and I look forward with a pleasing prospect of doing well in the army; and I hope, nothing will occur to blast my prospects, for my only wish for promotion is that you may enjoy it with me; I know also that it would be pleasing to your friends...”

From Waterloo to Melbourne, a life that shaped history

From Waterloo to Melbourne, a life that shaped history

RSM Thomas Barlow engaging one of Napoleon’s Cuirassiers

Apart from his military service, Thomas was a Methodist lay preacher and a man of strong religious belief.

“...while I am pursuing my military career, I hope by the afsistance of Divine Grace, I shall fight the good fight of faith and lay hold on Eternal Life. I feel the necefsity of taking up my Crofs Daily, thank god I have few temptations, and I know were they to increase, that if I put my trust in god he would deliver me from them, I still beg an interest in all your prayers that I may be preserved from all Sin and danger...”

Thomas distinguished himself during the battle by advancing into open ground to mark where the KDG should follow. He fought in hand-to-hand combat with a French Cuirassier, reputed to be the best swordsman in Europe at the time, disarming him in the process and taking him prisoner. By the end of fighting on the evening of Jun 18, 1815, he was one of only a handful of the Regiment and the senior NCO left standing. As a result, Thomas’ ambitions for “earthly honors” were realised. In recognition of his bravery, he was appointed Adjutant on August 18, 1815.

He continued his career with the KDG until April 16, 1818, when he transferred as a Captain to the 23rd Light Dragoon Guards and then became Adjutant of the Prince Regent’s 2nd Regiment of Cheshire Yeomanry in 1819. In that same year the Manchester Patriotic Union organised a demonstration at St Peter’s Field in Manchester. Unfortunately, the authorities believed the large crowd was becoming unruly, the Riot Act was read and the resulting cavalry charge left fifteen people dead, including a woman and child, with hundreds more wounded. The Cheshire Yeomanry were involved in the charge. Thomas’ commission was transferred in December of that year, the massacre at Peterloo having taken place the previous August.

Thomas and Elizabeth spent the following ten years in Cheshire adding to their family. Their first child Ann (given the second name, Waterloo) had been born in 1818 in Liverpool; Thomas Henry followed in 1820; William Wagstaff 1822; Margaret Rose 1827 and Mary in 1830. Sadly, Elizabeth died in 1830 leaving Thomas a widower with young children.

In 1833 Thomas retired from the army having married his second wife Sarah Dorrington on the 12 August that year. In 1841 they are living in Deansgate, Manchester where Thomas appeared to be pursuing a second career as a preacher. He was described by a contemporary as “...a bold soldierly man, who spoke in a very pompous style. His remarks from first to last were of a cutting and slashing nature.”

” The Commissioner informed me that some expressions in my defence were so scandalous, that he could not allow the case to be brought on; but would allow me to withdraw the defence and make out another. I replied that I could only make another similar; but then informed me that if I did, he would send me to gaol. My answer was that I would not be the first man who had been sent to gaol for telling the truth...No Sir! I am not a man to retract what I have said or written...I hope, therefore that you and the public will not form an unfavourable opinion of me through your statement.”

The outcome of the proceedings has not yet come to light, but Thomas lived to fight another day.

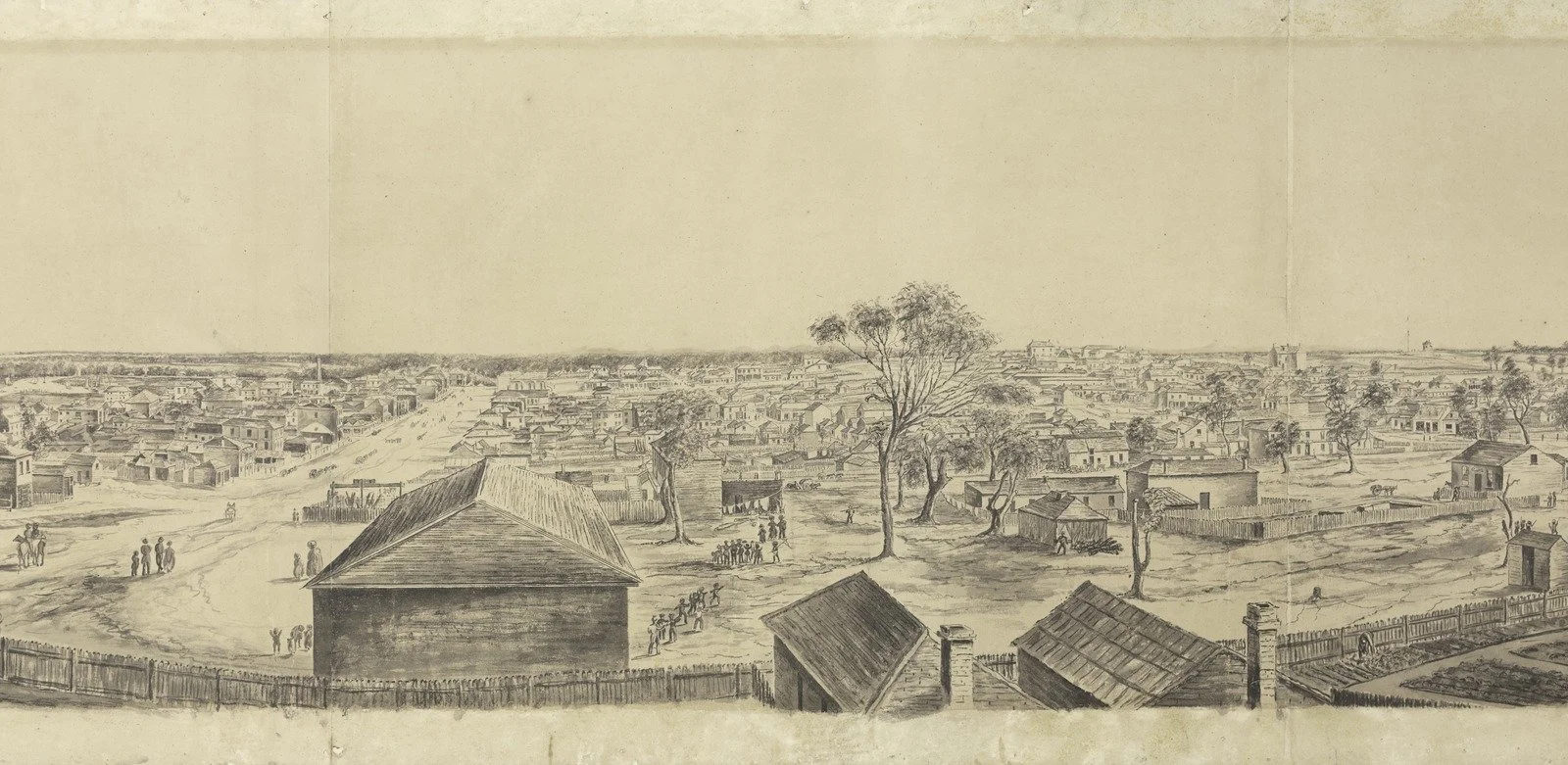

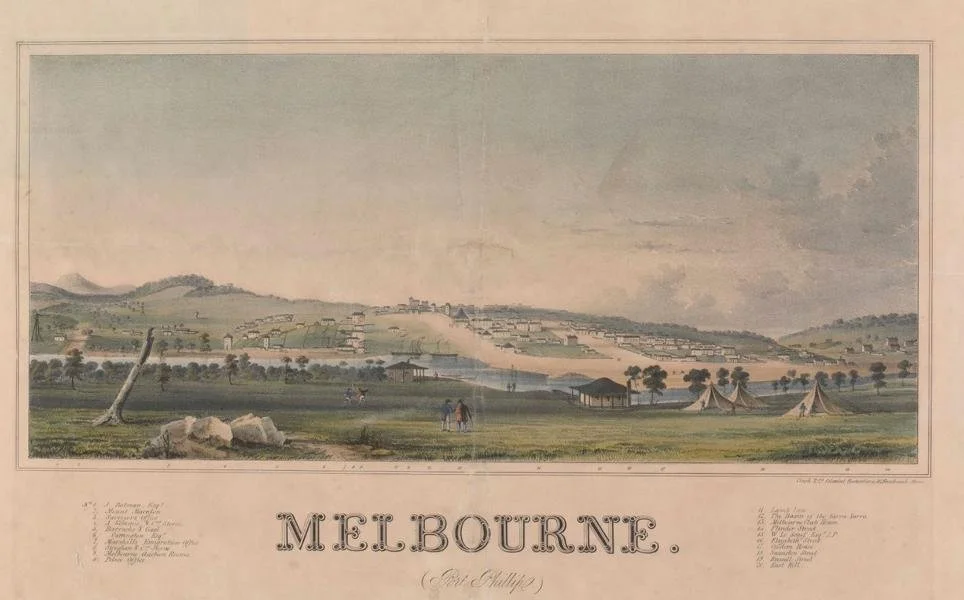

At this point it could be assumed that Thomas and Sarah would spend their retirement years reasonably quietly. However in 1849 they took passage to Australia on the ‘Courier’ arriving in Port Phillip on 11th September. On the passenger list Thomas’ occupation is described a schoolmaster. He and Sarah had been appointed by the United Kingdom Commissioner for Emigration schoolmaster and matron. Thomas’ duties were to provide instruction to the children on board and Sarah’s to look after the single immigrant women. It is without doubt his religious zeal had motivated his choice of vocation and he left his family behind in Bradford in the care of their grandparents. Unfortunately their voyage on the ‘Courier’ was troublesome. Thomas and Sarah’s enthusiastic preaching and hymn singing earned them the derision of the Master, and some of the crew and female immigrants.

An account of this is detailed in a history of the Belcher family, also ‘Courier’ migrants by Robert S. Belcher. Thomas appears to have been an enthusiastic citizen of the new colony, involving himself in the community. In an early book about the Port Phillip District, Thomas is described as a Congregational Minister who resided and ran a school at Nicholson Street, Collingwood. The school itself was run by the Wesleyan Association, and he was co-trustee along with others including Henry Frencham and Joseph Ankers Marsden.

Thomas seems to have had a falling out with his fellow trustees over the matter of a ten-pound loan and in April 1851, Thomas is fiercely defending his reputation in a letter to ‘The Argus’. He accuses the Argus of misrepresenting proceedings of a court case ‘Marsden and Frencham v Rev. Thomas Barlow’. The reporter states that Thomas had been ordered by the Commissioner to retract his plea as it contained certain remarks against the plaintiff, otherwise he would be sent to gaol for contempt and that a warrant had been made for his arrest. The content of the initial plea was only alluded to by the court reporter but were detailed in “Garyowen’s Melbourne” by its author Edmund Finn.

“The Reverend defendant filed a plea, and in this document, he set forth that one of the plaintiffs (J A Marsden) was a drunkard, a blackguard and a glutton.”

Finn questions the judgement of the Commissioner in allowing the defendant to resubmit in plea in less libellous terms. However, Thomas states that no retraction was requested and no warrant had been made, and he insists that the writer of the report has blackened his character.

Victoria's early colonial history, 1803-1851 - Victoria State Library

Thomas Creswick, The Iron Bridge, Shrewsbury, c.1840 (Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Scandals aside, In his adopted colony, he seemed determined to make his mark and help shape a better, more functional society.

In 1855, we find him addressing a public meeting advocating for the construction of a bridge across the Yarra River at Johnstone Street. This wasn’t a flight of fancy, it was a practical proposal, aligned with the 1837 survey of the Melbourne township and later reaffirmed in Superintendent La Trobe’s 1841 plan of proposed roads. The bridge, intended to span the river between Abbotsford and Kew would be a vital artery for trade and transport that would strengthen Melbourne’s eastern growth.

The original wooden bridge was completed in 1858—the same year Barlow passed away. In a rather poetic twist, the man who helped advocate for it never saw it finished.

*Barlow’s letters are held in the collection of the KDG museum and transcripts are available on request: www.qdg.org.uk

Thomas Barlow, 1785 - 1858

After a life that spanned continents and causes—from the thunderous fields of Waterloo to the pulpits of early Collingwood, Thomas died on May 10, 1858, at his home in Collingwood, and was laid to rest three days later at the Melbourne General Cemetery.

His wife Sarah followed him a decade later, closing a remarkable chapter in early colonial life.

Thomas devoted his final years to serving his adopted community, both spiritually and educationally.

A veteran, a preacher, a settler and a teacher, his was a life of duty, conviction, and quiet impact.

And this is where we pick up the story—in 2025

The Regiment have conducted an in-depth study into our man Barlow and had compiled an extraordinary amount of information about his life and service, but one crucial detail still eluded them: the location of his final resting place. They reached out to someone local in Australia with both ties to the Regiment and knowledge of Melbourne, to help solve the mystery.

What followed was some painstaking historical detective work, combing through archives, burial records, and the ageing registers of Melbourne General Cemetery.

Gradually, the fragments began to align, and after months of research, we were finally able to pinpoint the exact location of his grave.

Thomas Barlow’s final unmarked resting place…Melbourne General Cemetery.

Remarkably, Jill was already well ahead of us. She had been researching her own family tree, had uncovered Thomas Barlow herself, and had even visited our Regimental Museum in Cardiff back in 2011, a connection no one had noticed at the time.

She needed little convincing. Within days, Jill was heroically navigating a rainforest of forms and permissions to help bring Thomas Barlow’s story back into the light.

Now, this gripping story doesn't end there, once Thomas Barlow’s resting place was identified, a new challenge emerged: under regulations, only direct family members can authorise work on an existing grave. To proceed, we had to find a living relative.

With the help of some tireless family-history sleuths, we traced a very distant descendant living in Brisbane... Mrs Jill Birtwistle.

So, with the resting place found, unmarked, we of course just couldn't walk away and leave this site empty....the natural next step was to honour Thomas by creating a fitting memorial for such a fascinating veteran and settler.